Frederick Sandys

Sandys, Antony Frederick, A.N., generally called Frederick Sandys, sometimes F. K. Sandys from his habit of signing the name Frederick thus, “Fk. Sandys.” This clever artist was bom at Norwich in 1832,[1] and educated at the Norwich Grammar School, applying himself at a very early age with earnestness to drawing and painting. He never attended the Royal Academy Schools as has been stated, and was not a pupil either of Richmond or Lawrence. Lawrence he never met but for a few minutes, and his acquaintance with Richmond was only as that of a family friend, and never the relationship of pupil and teacher. His early life is said to have been influenced by the work of Menzel, but this also is an error, as never but once did he see illustrations of the work of this artist, and he himself stated that they made no impression whatever upon him. His education in art was entirely the work of local Norfolk art teachers and his own strenuous industry when he came to London and worked on his own account, copying pictures in the National Gallery.

His earliest exhibit at the Royal Academy was in 1851, before he was twenty-one years old, when he sent in a crayon portrait of Lord Henry Loftus, following it in 1854 by a smaller one of the Rev. Thomas Freeman, of Norwich. In 1856 he sent in two crayon portraits, one an anonymous one, and the other representing the Rev. Thomas Randolph. His first exhibits in oil were two pictures sent in 1861, one called Oriana, and the other a portrait of Mrs. W. H. Clabburn, of Thorpe, Norwich. It was about this time that he commenced to do some illustrations for periodicals, and his first drawing was entitled Portent, done for the Cornhill Magazine in 1860. In 1861 he commenced to work for Once a Week, and during that and the following year produced eleven important illustrations as follows: Yet once more on the Organ Play, The Three Statues of Ægina, From my Window, Rosamond, Queen of the Lombards, The Sailor’s Bride, The King at the Gate, Jacques de Caumont, The Old Chartist, Harald Harfagr, The Death of King Warwulf, and The Boy Martyr. In the same year he did Manoli for the Cornhill Magazine, and Until Her Death for Good Words. His exhibits in the Royal Academy in 1862 were various. There were two pictures in oil, Mrs. Clabburn, senior, and King Pelles’ Daughter bearing the Vessel of the Holy Grail, one in crayons of Mrs. Doulton, a pen-and-ink drawing of Autumn, and another of Mrs. Anderson Rose. In 1863 his drawing for Sleep appeared in Good Words, and The Waiting Time in the Churchman’s Magazine, while to the Academy he sent in three oil portraits, one representing Mrs. Anderson Rose, the same lady whom he had exhibited in pen-and-ink in the previous year, a picture of most marvelous execution, and two fancy portraits called Vivien and La Belle Ysonde.

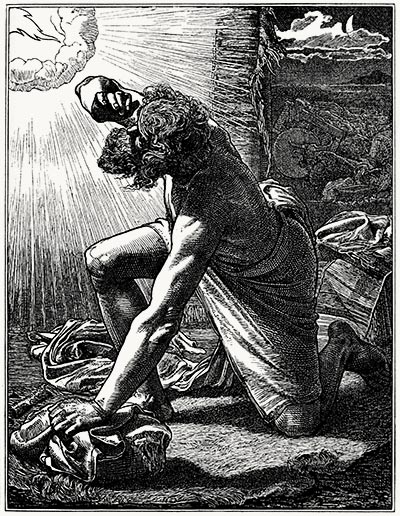

The oil portrait that was perhaps his greatest achievement was seen at the Academy in 1864. It was called A Portrait, but represented Mrs. Jane Lewis, of Roehampton, and was a most wonderful example of elaborate miniature manipulation, almost perfect in its execution. With it he sent an oil picture called Morgan Le Fay, and a pen-and-ink drawing of Judith. Two oil pictures appeared in 1865, Cassandra, and Gentle Spring, and a grand illustration in the Shilling Magazine, called Amor Mundi. In 1866 his notable oil painting of “Lady Rose” was exhibited, and his work appeared in the Argosy, Quiver, Once a Week, and the Cornhill Magazine, the following being the titles of pictures respectively: If, The Advent of Winter, Cassandra and Helen, and Cleopatra.

In 1868 he returned in his Royal Academy exhibits to his earlier medium of crayons, sending in the Study of a Head, and a portrait of Mr. George Critchett. With them was sent in his great picture of Medea, which was accepted, but rejected at the last moment.

This procedure drew forth from his friends an indignant protest, and started a severe correspondence in the Times, with a characteristic eulogy of the picture from Mr. Swinburne, with the result that in the following year the picture was hung on the line, and with it was accepted a crayon portrait of Mrs. Barstow. In 1871 another oil portrait was sent in, representing Mr. W. H. Clabburn, a crayon portrait of the same person, and a group in crayons of the children of Mr. J. J. Colman. Four crayon portraits appeared in 1873, representing Mrs. William Brand, Mr. Leopold de Rothschild, Mr. Frederick A. Millbank, and Mrs. Millbank. His exhibits in 1875 were a crayon portrait of Father Rossi, another of Miss Ellis, one without a name, and an oil painting of Mrs. William Brand. In 1876 he exhibited one crayon portrait only, Mrs. Charles Augustus Howell, in 1878 a similar one of Mr. Cyril Flower (now Lord Battersea), and in 1879 an oil portrait of Mrs. Temple Soanes. His exhibits in 1880, 1882, and 1883 were all in crayons, the two portraits in 1880 representing James Brand, Esq., and Ethel and Mabel; those in 1882, Mr. Robert Browning, His Excellency the Hon. J. Kussell Lowell, Mr. Matthew Arnold, and Professor Goldwin Smith. In that year he had an important illustration in Dalziel’s Family Bible, entitled Jacob hears the Voice of the Lord. In 1883 he sent into the Academy a crayon portrait of Mrs. H. Chinnery, and in 1886 his last exhibit was an oil portrait of Mr. William Gillilan.

The important work of Sandys was, however, by no means confined to his exhibits at the Royal Academy and his book illustrations. He first of all came before the public in connection with a clever satire of the pictures exhibited by Millais at the Royal Academy in 1857, called Sir Isunbras at the Ford. Sandys’ parody of the picture was a very brilliant drawing, representing Millais, Rossetti, and Holman Hunt riding upon a donkey, inscribed "J. R. Oxon", and intended to represent Ruskin. The joke was directed against the Oxford Professor on account of his over-vehement championship of Rossetti and Holman Hunt. It was the occasion of the first meeting between Rossetti and Sandys, and as the former artist had sufficient sense of humour to take the satire in good part, it was the beginning of a warm friendship which sprang up between the two men, and lasted uninterruptedly until Rossetti’s death.

A little later on Sandys took up his abode in Kensington, and became associated with that wonderful circle which included Swinburne and George Meredith, Tennyson and the Brownings, Burne-Jones, Madox Brown, William Morris, and others. It was from that time that his illustrative Work commenced, as previous to then in book illustration he had only executed some pictures for the Birds of Norfolk and the Antiquities of Norwich.

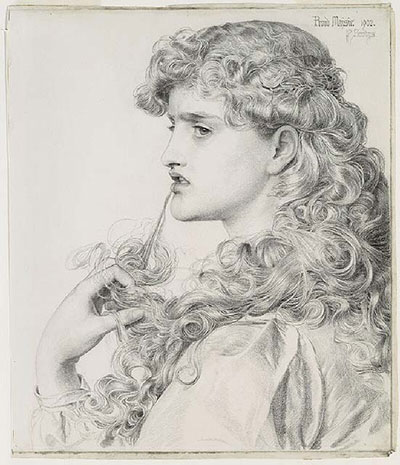

There are many works by him which were never exhibited at the Royal Academy, but that must be mentioned. In 1862 he painted three notable oil pictures, Fair Rosamond, A Vestal Offering Her Hair on a Rose-Crowned Altar, and Mary Magdalene. In 1868 his wonderful crayon drawing called Proud Maisie appeared, perhaps the most vivid and dramatic work he ever executed, while in the same year he produced several symbolic figures, notable amongst which were Lethe, Proserpine, Fate, Penelope, and Miranda. Amongst his crayon portraits should also be mentioned Bishop Denison, of Salisbury, the Misses Clabburn, Lady Buxton, 1875; Lady Lawrence, Mrs. Samuel Hoare and her children, 1884; Mrs. George Meredith and Miss Meredith, Mrs. Cyril Flower (now Lady Battersea), and Miss Clara Flower, 1872; Miss Christabel Gillilan, 1887; Mrs. H. P. Sturgis, 1894; Mrs. Palmer, 1896; St. George, 1880, and others. About the year 1880 Sandys received a commission from Messrs. Macmillan & Co. to execute a series of crayon portraits of well-known literary persons, and he devoted many years to this work. The series, which remains in the possession of Messrs. Macmillan, includes portraits of Robert Browning, Matthew Arnold, John Morley, J. H. Shorthouse, Lord Tennyson, Dean Church, Dr. Westcott, J. R. Green, Lord Wolseley, and Mrs. Oliphant, while in 1891 he produced a delightful portrait of the children of Mr. Alexander Macmillan, and in the following year, portraits of the same persons, two girls, entitled A Christmas Carol.

Rossetti pronounced Sandys to be the greatest of living draughtsmen, and his exquisite skill in drawing is well represented in the wonderful picture of Proud Maisie, now belonging to Dr. Todhunter, and in the studies of foliage, tree-trunks, branches and figures in which the artist delighted. He was never a member of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, nor in fact was he associated with any society of artists at all. He lived in constant revolt against the Academy and all its works, and was in frequent conflict with every other artistic society, pursuing a resolute and lifelong independence of all schools, teachers and societies, and a warfare more or less with most artists. The methods and ideals, however, of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were his, and his picture of Autumn, exhibited in 1862, is a wonderful example of the work of this school of artists, carried out to a logical issue, and with marvelous perfection. It is probable, however, that the reputation of Sandys will rest mainly upon his portraits of Mrs. Anderson Rose, 1863, Mrs. Jane Lewis, 1864; and Medea, 1869. These are luminous and forcible works, brilliant in colouring, full of detail, and exquisitely finished. They partake strongly of a sympathy with early Flemish work, especially being reminiscent of such masters as Van Eyck, Van der Weyden, and Memling. From these men he learned “that real regard for truthful expression in subject and detail which the pre-Raphaelites found blended with more spiritual qualities in fourteenth-century Florentine art.”

Towards the latter part of his life Sandys devoted himself to crayon studies, which exhibit his remarkable technical dexterity and his decorative feeling for minute details. As a draughtsman, his line in the modelling of the beauty of a head was full of exquisite sensitiveness and nervous musical quality.

He had a marvellous sense of form, but he was curiously lacking in the power of felicitous indication and in imaginative understanding. His crayon studies, exquisitely beautiful though they were, did not enhance his reputation, and it is for his handling of the primitive Flemish technique of oil painting, and for the certainty of his work in his half-dozen great pictures that he will be praised. Of his personal life it is hardly safe to say anything, so completely did he ruin his chances of a great reputation by his blameworthy and pitiable career.

As recently as March 1894 there was an exhibition of his works at the Leicester Gallery, London, arranged by his stalwart supporter Mr. Ernest Brown, and the catalogue had a judicious preface by Mr. F. G. Stephens, who is now almost the last of the little band who worked with such earnestness and devotion under the influence of the pre-Raphaelite Movement. One of the finest of his works then exhibited was a full-length study of a girl called “My Lady Greensleeves,” now in the possession of Mr. J. S. Budgett of Stoke Park, Guildford.

Sandys has frequently been the subject of magazine and other articles, but the only thoroughly reliable notice of his life and works appeared as the winter number of The Artist, Nov. 18, 1896. It was written by Esther Wood, and was issued with extra illustrations in specially choice form, quarto, 150 copies only, and folio, twenty copies only. From this memoir and from personal acquaintance most of the above information is taken. There were articles upon him in the Art Journal, 1884, by Mr. J. M. Grav, and others by the same author in the Hobby Horse of 1888 and 1892, while Mr. Pennell wrote respecting Sandys in Pan, a German publication, in 1895, and later on in the Savoy,[2] 1896, and the Quarto, 1896. His engraved works are alluded to by Gleeson White in his English Illustration,[3] and they are illustrated in the Art Journal, 1894, Cornhill Gallery, 1865, Savoy, 1896, Quarto, 1896, Hobby Horse, 1888, Pan, 1895, Thorobury’s Historical Ballads, 1876, Pennell’s Modern Illustration, Pictures of Society, 1866, Idyllic Pictures, 1867, and Pennell’s Pen Drawing and Pen Draughtsmen, 1894. Some of his works were exhibited at Mr. Ganihart’s Gallery, and nine were hung at the Grosvenor Gallery.

Appendix I: Joseph Pennell On Frederick Sandys

In 1865, there must have been almost as many good illustrated magazines published in England alone as there are today in the whole world. Besides Good Words, the Cornhill, and Once a Week, there were London Society, the Shilling Magazine, the Argosy, and the Quiver. The uniform edition of Dickens was also being issued; illustrated by C. Green, Luke Fildes, Marcus Stone, J. Mahoney and F. Barnard.

F. Sandys is, in imaginative power, the greatest of all these artists; in technique he is the legitimate successor of Durer, in popularity he is a hopeless failure. He has never illustrated a book: so far as I know, so made but few drawings specially for books: these few are contained in Willmot’s Sacred Poetry, 1863, Life’s Journey, the Little Mourner, and Dalziel’s Bible Gallery.

In 1861, a number of his drawings were printed in Once a Week: Yet Once More Let the Organ Play, Three Statues of Ægina, and others. In every one is seen the hand of the man able to carry on the tradition of Durer, and yet bring it into line with modern methods. So far as I am aware, Ruskin never mentions him; how far this was owing to the famous Sir Isumbras caricature, The Nightmare, I do not know. All the spirit of early German art breathes through his drawings. But it is during the next year, 1862, that Sandys, becoming accustomed to the wood-block, did some of his most powerful work: The Old Chartist, Harold, and King Warwulf, in Once a Week. In The Old Chartist there is the real Dürer feeling in the distant landscape, but the trees are better than Dürer’s trees, and the figure is one that Sandys has seen for himself. But in all his work there is this evidence of things seen and studied.

1862 was his most productive year; in 1863 there are but four drawings; none in 1864; in 1865, a magnificent Amor Mundi, for Miss Rossetti’s poem, printed in the April number of the Shilling Magazine. After that there are only one or two, and then he disappears. There are many drawings by him on paper, but it is safe to say no man who did so few drawings on wood ever made such a reputation. True, Whistler only did four in Once a Week (1861-2), among them the charming design printed in this article, but he was known as an etcher and painter at the time.

Appendix II: Gleeson White On Frederick Sandys

This most admirable illustrator was born in Norwich in 1832,[4] the son of a painter of the place, from whom he received his earliest art instruction. Among his first drawings was a series of illustrations of the birds of Norfolk, and another dealing with the antiquities of his native city. Probably he first exhibited in 1851, with a portrait (in crayons) of ‘Henry, Lord Loftus’ which appears as the work of ‘F. Sands’ in the catalogue of the Royal Academy to whose exhibitions he has contributed in all forty-seven pictures and drawings.[5]

The above, extracted from Mr. J. M. Gray’s article, Frederick Sandys and the Woodcut Designers of Thirty Years Ago, gives the facts which concern us here. A most interesting study of the same artist by the same critic, in the Art Journal,[6] supplies more description and analysed appreciation. The eulogy by Mr. Joseph Pennell in the Quarto[7] must not be forgotten. Further references to Mr. Sandys appear in a lecture delivered by Professor Herkomer at the Royal Institution, printed in the Art Journal, 1883, and in a review of Thornbury’s Ballads by Mr. Edmund Gosse in the Academy.[8]

It is quite possible, although only thirteen of the thirty or so of illustrations by Frederick Sandys appeared in Once a Week, that these thirteen have been the most potent factor in giving the magazine its peculiar place in the hearts of artists. The general public may have forgotten its early volumes, but at no time since they were published have painters and pen-draughtsmen failed to prize them. During the years that saw them appear there are frequent laudatory references in contemporary journals, with now and again the spiteful attack which is only awarded to work that is unlike the average. Elsewhere mention is made of articles upon them which have appeared from time to time by Messrs. Edmund Gosse, J. M. Gray, Joseph Pennell, and others. During the “seventies,” no less than in the “eighties” or “nineties,” men cut out the pages and kept them in their portfolios; so that today, in buying volumes of the magazine, a wise person is careful to see that the “Sandys” are all there before completing the purchase. Therefore, should the larger public admit them formally into the limited group of its acknowledged masterpieces, it will only imitate the attitude which from the first fellow-artists have maintained towards them.

The original drawings, If, Life's Journey, The Little Mourner, and Jacques de Caumont, were exhibited at the “Arts and Crafts,” 1893. That a companion volume to Millais’s Parables, with illustrations of The Story of Joseph, was actually projected, and the first drawings completed, is true, and one’s regret that circumstances—those hideous circumstances, which need not be explained fully, of an artist’s ideas rejected by a too prudish publisher—prevented its completion, is perhaps the most depressing item recorded in the pages of this volume.

That some thirty designs all told should have established the lasting reputation of an artist would be somewhat surprising, did not one realise that almost every one is a masterpiece of its kind. At the risk of repeating a list already printed and reprinted, it is well to condense the scattered references in the foregoing pages in a convenient paragraph:

The Cornhill Magazine : The Portent (’60), Manoli (’62), Cleopatra (’66) ; Once a Week : Yet once more on the organ play, The Sailor’s Bride, From my window, Three Statues of Ægina, Rosamund Queen of the Lombards (all 1861), The Old Chartist, The King at the Gate, Jacques de Caumont, King Warivolf, The Boy Martyr, Harold Harfagr (all ’62), and Helen and Cassandra (’66); Good Words: Until her Death (’62), Sleep (’63); Churchman’s Family Magazine: The Waiting Time (’63); Shilling Magazine: Amor Mundi (’65); The Quiver: Advent of Winter (’66); the Argosy: If (’65) ; the Century Guild Hobby Horse: Danae (’88); Wilmot’s Sacred Poetry: Life's Journey, The Little Mourner; Cassell’s Family Magazine: Proud Maisie (’81); and Dalziels’ Bible Gallery: Jacob hears the voice of the Lord.

In addition, it may be interesting to add notes of other drawings : The Nightmare[9] (1857) a parody of Sir Isumbras at the Ford, by Millais, which shows a braying ass marked “J. R.” (for John Ruskin), with Millais, Rossetti, and Holman Hunt on his back;Morgan le Fay, reproduced as a double-page supplement in the British Architect, October 31, 1879; a frontispiece, engraved on steel by J. Saddler, for Miss Muloch’s Christian’s Mistake (Hurst and Blackett), and another for The Shaving of Shagpat (Chapman and Hall, 1865); a portrait of Matthew Arnold, engraved by O. Lacour, published in the English Illustrated Magazine, January 1884; another of Professor J. R. Green, engraved by G. J. Stodardt, in The Conquest of England, 1883 ; and one of Robert Browning, published in the Magazine of Art shortly after the poet’s death; Miranda, a drawing reproduced in the Century Guild Hobby Horse, vol. iii. p. 41; Medea, reproduced (as a silver-print photograph) in Col. Richard’s poem of that name (Chapman and Hall, 1869); a reproduction of the original drawing for Amor Mundi, and studies for the same, in the two editions of Mr. Pennell’s Pen-Drawing and Pen-Draughtsmen (Macmillan); a reproduction of an unfinished drawing on wood, The Spirit of the Storm, in the Quarto (No. i, 1896); Proud Maisie in Pan (1881), reissued in Songs of the North, and engraved by W. Spielmayer (from the original in possession of Dr. John Todhunter) in the English Illustrated Magazine, May 1891, and the original drawing for the Advent of Winter and one of Two Heads, reproduced in J. M. Gray’s article in the Art Journal(March 1884).

To add another eulogy of these works is hardly necessary at this moment, when their superb quality has provoked a still wider recognition than ever. Concerning the engraving of some Mr. Sandys complained bitterly, but of others, notably the Danae, he wrote in October 1880 : My drawing was most perfectly cut by Swain, from my point of view, the best piece of wood-cutting of our time—mind I am not speaking of my work, but Swain’s.

To see that the artist’s complaint was at times not unfounded one has but to compare the Advent of Winter as it appears in a reproduction of the drawing (Art Journal, March 1884) and in the Quiver. It was my best drawing—entirely spoilt by the cutter,

he said; but this was perhaps a rather hasty criticism that is hardly proved up to the hilt by the published evidence.

As a few contemporary criticisms quoted elsewhere go to prove, Sandys was never ignored by artists nor by people of taste. Today there are dozens of men in Europe without popular appreciation at home or abroad, but surely if his fellows recognise the master-hand, it is of little moment whether the cheap periodicals ignore him, or publish more or less adequately illustrated articles on the man and his work. Frederick Sandys is and has been a name to conjure with for the last thirty years. Though still alive, he has gained (I believe) no official recognition. But that is of little consequence. There are laureates uncrowned and presidents unelected still living among us whose lasting fame is more secure than that of many who have worn the empty titles without enjoying the unstinted approval of fellow-craftsmen which alone makes any honour worthy an artist’s acceptance.

The main article reproduces the entry for Frederick Sandys as published in Bryan’s Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, vol. 5, published in London by G. Bells and Sons, Ltd., 1925. Appendix I is an exerpt taken from the article entitled “A Golden Decade in English Art”, published in issue N° 1 of the Savoy, January 1896. Appendix II is an exerpt taken from English Illustration, "the Sixties" written by Gleeson White and published in Westminster by Archibald Constable and Co., 1903.

-

- ^ Recent authors usually state 1829 as Sandys's date of birth. He died in 1904.

- ^ See appendix I.

- ^ See appendix II.

- ^ See note on first page.

- ^ Century Guild Hobby Horse, vol.iii p. 47 (1888).

- ^ March 1884.

- ^ No. I, 1896.

- ^ 1876, i. 176.

- ^ A large broadsheet reproduced by some lithographic process.

- Image sources:

Norfolk Museums; The National Gallery of Canada; the Internet Archive